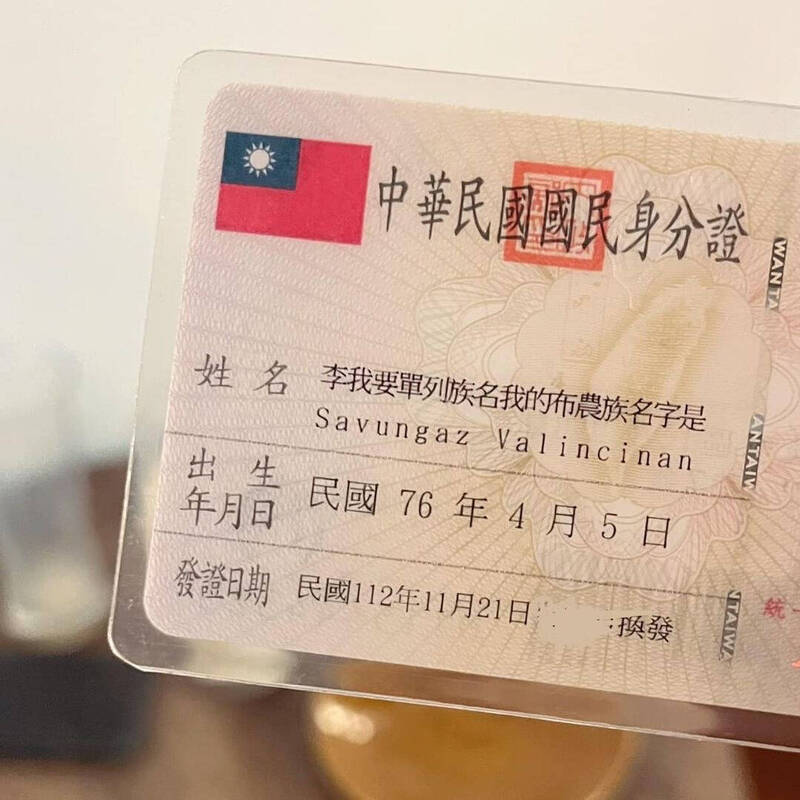

A candidate for the Indigenous constituency in Taiwan’s Legislature has, in protest over government policies mandating the use of Chinese characters, changed her name to “李我要單列族名我的布農族名字是Savungaz Valincinan,” which translates as “Li I want to list my tribal name separately; my Bunun name is Savungaz Valincinan.”

(photo by Savungaz Valincinan)

Here’s a ChatGPT translation of a story in the Liberty Times about this:

The registration of candidates for the 2024 legislative election concluded on the 24th. According to data from the Central Election Commission (CEC), there are a total of 10 candidates running for mountain indigenous legislator positions. One candidate stands out with a name that spans 34 characters, and it reads, “李我要單列族名我的布農族名字是Savungaz Valincinan,” making it the longest name among this year’s legislative candidates.

Following the successful administrative lawsuit regarding the “Administrative Appeal for Single Listing of Tribal Names on Indigenous Identification Cards” in early November, the New Taipei City Government Civil Affairs Bureau issued the first identification card with a single-listed tribal name. However, as this was a local “case remedy,” other indigenous individuals wishing to list only their tribal names are still unable to complete the process.

Savungaz Valincinan expressed that for this election, she chose not to use the transliteration of her Bunun tribal name in Chinese characters. Two days before registration, she officially changed her name at the household registration office to “李我要單列族名我的布農族名字是Savungaz Valincinan.”

Emphasizing that the name change is not a mere joke but a sincere and poignant appeal, Savungaz Valincinan questioned, “Why should such a small matter like adjusting administrative procedures make us shout so hard and still be unattainable?”

Other indigenous individuals have also inquired with local governments about listing only Romanized Pinyin for their names. However, according to the responses received, currently, there are only three options: traditional name transliterated into Chinese characters, traditional name transliterated into Chinese characters with Romanized Pinyin, and Chinese name alongside traditional name with Romanized Pinyin.

She urged that if the government continues to overlook the demands of indigenous people, and if she is fortunate enough to become a legislator in the future, every government official addressing her must recite the “demand for single-listing tribal names” every time until they genuinely amend the administrative procedures.

In the 2024 legislative election, aside from the 315 regional legislative candidates, there are 10 candidates for plain indigenous legislator positions and 10 candidates for mountain indigenous legislator positions who have completed their registrations.

For more about this general topic, please see Some Indigenous people in Taiwan want to drop their Chinese names: ‘That history has nothing to do with mine’, an excellent article by Stephanie Yang and David Shen (Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2023).

source: 34 zì! Míngnián dàxuǎn míngzi zuìcháng Lìwěi cānxuǎn rén — pàn zhèngfǔ zhòngshì dān liè zúmíng sùqiú (34字!明年大選名字最長立委參選人 盼政府重視單列族名訴求), Liberty Times, November 26, 2023.

further reading: Savungaz Valincinan Facebook page.

I note the article is using “Romanized Pinyin” to refer to the written form of the indigenous name (I guess this is the case in the original article, not a ChatGPT artefact). It’s fairly common to see “Pinyin” used as a genericized term for romanization systems, even for languages other than Mandarin Chinese. However, in this case, I may be mistaken but I believe the Latin alphabet is the standard writing system for the Bunun language, so technically this isn’t “romanization” at all. We wouldn’t usually say that written Vietnamese, for example, is romanized; it’s just the way it’s written nowadays.

Good point, Jonathan.

The original article does indeed have, as you suspected, “羅馬拼音” (Luómǎ pīnyīn) three times. But long experience has taught me not to expect precision from the media when it comes to matters of romanization. The lede of the article, for example, isn’t about the candidate’s quest to have — and this is going to sound odd in short form — her name serve as her name but rather focuses on the quirkiness of having a really long official name.

Your comment also tangentially raises an issue I haven’t addressed directly before: “Pinyin” vs. “pinyin.”

In the past, I may have been somewhat lax in how I approached capitalization of this term. But in recent years I’ve tried to be more consistent: using the capitalized form when “Pinyin” is used as a short form for “Hanyu Pinyin.” And I have tried to avoid using “pinyin” as a general term.

Pingback: Writing indigenous names in Taiwan - Language Miscellany