Late last year a police officer in Taichung (Taizhong), Taiwan, was checking on a fifty-something-year-old woman when he made the mistake of addressing her as “ama” (Taiwanese for “grandmother,” and generally preferred here to Mandarin forms for elderly women).

Addressing a fifty-something Taiwanese woman even as “ayi” (auntie) would be inadvisable, assuming, of course, she’s not your actual aunt. But “ama”?

I pity the fool.

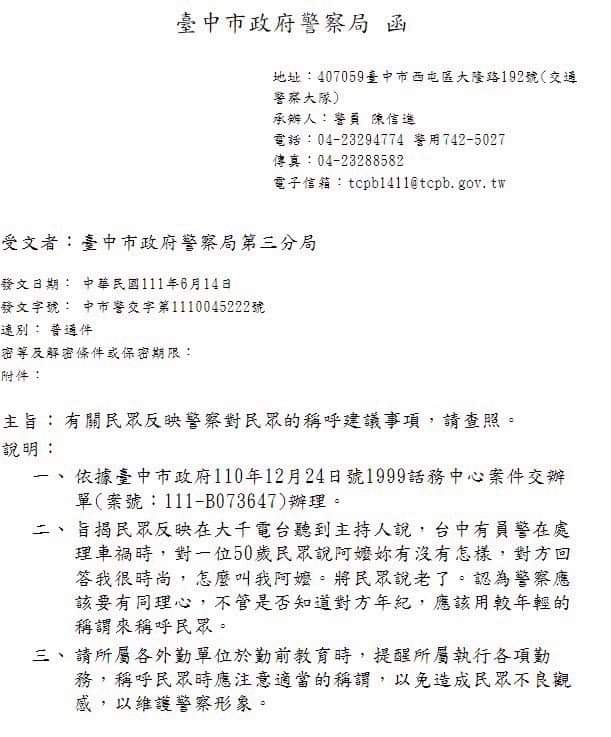

In response to complaints, the police have come up with guidelines for how to address members of the public, and most terms are now discouraged.

Tǒngyī lǜ dìng 4 zhǒng chēnghu, rúguǒ shì niánqīng rén, kàn shì xuéshēng, bù fēn nánnǚ, tǒngyī chēnghu “tóngxué,” rúguǒ shì niánqīng nǚxìng, tǒngyī chēnghu “xiǎojiě,” zīshēn (niánzhǎng) nǚxìng zé shì tǒngyī chēnghu “nǚshì,” zhìyú nánxìng, chúle niánqīng xuéshēng zhī wài, dōu chēnghu “xiānshēng.”

統一律定4種稱呼,如果是年輕人、看似學生,不分男女,統一稱呼「同學」,如果是年輕女性,統一稱呼「小姐」,資深(年長)女性則是統一稱呼「女士」,至於男性,除了年輕學生之外,都稱呼「先生」。

So there are now four categories:

- young people (regardless of gender) who look like students: tóngxué (a term used to refer to students or one’s classmates)

- young women: xiǎojiě (miss, Ms.)

- older women: nǚshì (this one’s tricky; it’s more formal than “ma’am”; more like “madame,” I suppose).

- men who look older than students: xiānshēng (mister, sir)

As I remarked above, “nǚshì” is a bit tricky, but not just in terms of translation. It’s quite formal and something people usually would write rather than say. Consider, for example, how one might begin a letter to a stranger “Dear [name]”; but if you were standing in front of that person you would not begin a conversation with them with the same words.

So, if in doubt, call a Taiwanese woman “xiǎojiě.” But calling a Chinese woman “xiaojie” is not a good idea these days (if not used in combination with a surname), though it was fine when I lived in China back in the early 1990s.

By the way, if you ever need to see if a font face will handle Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks well, “nǚshì” is an excellent test word, as “ǚ” is the combination of letter and tone least likely to be supported.

Further reading: