Today I’d like to talk about a sign at a stand that sells guabao, a quintessential Taiwanese snack.

I took my own photo, but it didn’t make the guabao look particularly appetizing, so I’m using a public-domain image instead so you can see what one looks like if you don’t already know. But when I buy one I have them leave off the cilantro/xiāngcài. I hate that stuff.

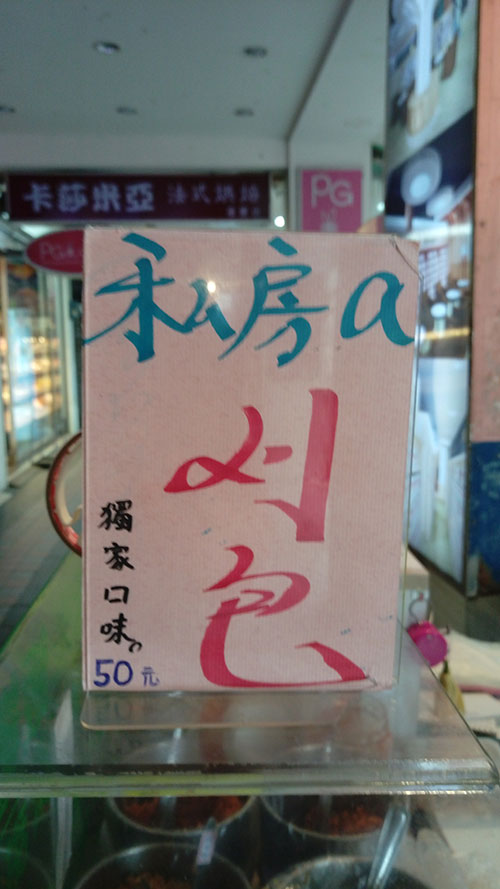

Here’s the sign.

刈包

獨家口味

50元

(NT$50 is about US$1.50.)

The sign uses some Taiwanese, specifically “a刈包.” If the whole thing were in romanized Taiwanese, it would be

koah-pau

To̍k-ka kháu-bī

50 îⁿ

But parts of that are unidiomatic, as Taiwanese expert Michael Cannings informs me. (Alas, my Taiwanese sucks.) So this is a sign in both Taiwanese and Mandarin, which isn’t particularly surprising given that guabao is a Taiwanese food but most people in northern Taiwan use Mandarin most of the time. (I’m using the spelling “guabao” rather than “koah-pau” in most of this post because this is a Pinyin site.)

Something about this sign did surprise me a lot. Can you guess?

- It’s not the use of a Roman letter — I should probably say “English letter” in this case, since here the letter is meant to be pronounced much like the “A” in “ABC” — though regular readers know that’s certainly more than enough to get me interested.

- It’s not that the sign has “刈包” rather than “割包” for guabao. In searches restricted to .tw domains, Google returns 181,000 results for “刈包” and just 41,900 results for “割包”, even though Taiwan’s Ministry of Education prefers the latter form. Even on government Web pages “刈包” beats “割包” by a ratio of more than two to one.

- It’s not the style in which “刈包” is written by hand, though I kinda like that.

- And it’s not even that “a” was used instead of a different Roman letter: “ê”.

What seems to me most distinctive about this sign is that the Roman letter appears in lowercase rather than as “A”.

A single letter being used to represent a Sinitic morpheme in a text otherwise in Chinese characters is almost always written in upper case, e.g., A菜, 宮保G丁, K書. (Oh, that reminds me: I really need to answer that e-mail message about K. Sorry, Steven.)

In other words, if a sign is going to have the Roman letter “a” stand in for the Taiwanese possessive particle (the equivalent of Mandarin’s de/的), I would expect in this particular case for the sign to have “私房A” rather than “私房a”. I’m pleased by the use of lowercase; capital letters should be mainly for proper nouns and the beginnings of sentences.

It’s probably a one-off. But just in case I’ll be on the lookout to see if there’s a trend toward greater use of lowercase.

The text also presents a challenge: How should this be written in Pinyin? The last part (獨家口味 / 50元) is easy, because it’s just straight modern standard Mandarin:

50 yuán

But what to do with this?

刈包

Probably this:

guabao