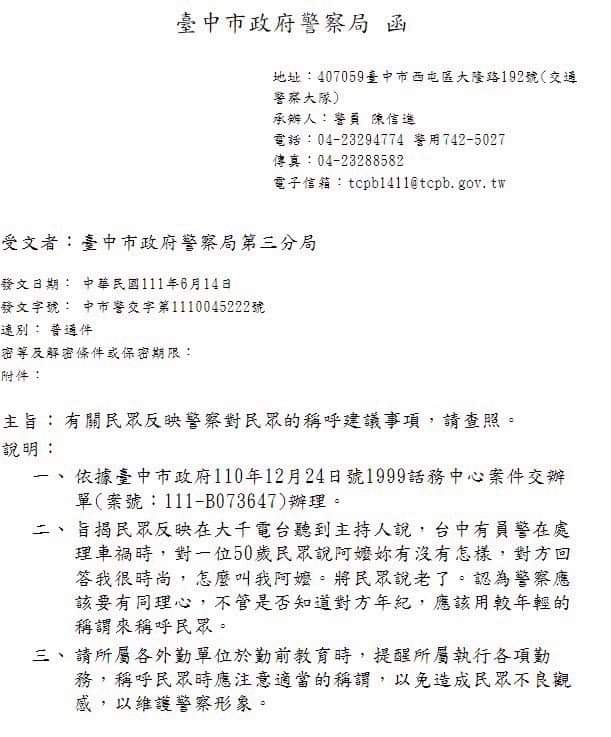

Late last year a police officer in Taichung (Taizhong), Taiwan, was checking on a fifty-something-year-old woman when he made the mistake of addressing her as “ama” (Taiwanese for “grandmother,” and generally preferred here to Mandarin forms for elderly women).

Addressing a fifty-something Taiwanese woman even as “ayi” (auntie) would be inadvisable, assuming, of course, she’s not your actual aunt. But “ama”?

I pity the fool.

In response to complaints, the police have come up with guidelines for how to address members of the public, and most terms are now discouraged.

Tǒngyī lǜ dìng 4 zhǒng chēnghu, rúguǒ shì niánqīng rén, kàn shì xuéshēng, bù fēn nánnǚ, tǒngyī chēnghu “tóngxué,” rúguǒ shì niánqīng nǚxìng, tǒngyī chēnghu “xiǎojiě,” zīshēn (niánzhǎng) nǚxìng zé shì tǒngyī chēnghu “nǚshì,” zhìyú nánxìng, chúle niánqīng xuéshēng zhī wài, dōu chēnghu “xiānshēng.”

統一律定4種稱呼,如果是年輕人、看似學生,不分男女,統一稱呼「同學」,如果是年輕女性,統一稱呼「小姐」,資深(年長)女性則是統一稱呼「女士」,至於男性,除了年輕學生之外,都稱呼「先生」。

So there are now four categories:

- young people (regardless of gender) who look like students: tóngxué (a term used to refer to students or one’s classmates)

- young women: xiǎojiě (miss, Ms.)

- older women: nǚshì (this one’s tricky; it’s more formal than “ma’am”; more like “madame,” I suppose).

- men who look older than students: xiānshēng (mister, sir)

As I remarked above, “nǚshì” is a bit tricky, but not just in terms of translation. It’s quite formal and something people usually would write rather than say. Consider, for example, how one might begin a letter to a stranger “Dear [name]”; but if you were standing in front of that person you would not begin a conversation with them with the same words.

So, if in doubt, call a Taiwanese woman “xiǎojiě.” But calling a Chinese woman “xiaojie” is not a good idea these days (if not used in combination with a surname), though it was fine when I lived in China back in the early 1990s.

By the way, if you ever need to see if a font face will handle Hanyu Pinyin with tone marks well, “nǚshì” is an excellent test word, as “ǚ” is the combination of letter and tone least likely to be supported.

Further reading:

- Chinese terms of address for single ladies. Victor Mair, Language Log, August 6, 2012.

- “Wǒ hěn shíshàng, zěnme chēnghu wǒ ‘āmā’?” (「我很時尚,怎麼稱呼我阿嬤?」). Ziyou Shibao (Liberty Times), June 16, 2022.

- https://www.facebook.com/NPAMEME/posts/1475752322884512

- Covert Sexism in Mandarin Chinese, by David Moser. Sino-Platonic Papers 21. January 1997.

A female former student and friend, about age 50, a native Taiwanese bendi ren, who now teaches Mandarin at the US language training center in Monterey CA, commented:

This topic is very personal, LOL. I was teaching “大媽” [dàmā] the other day and I said “older women like me”. I have a feeling that 大媽 are women who don’t work and have a lot of free time in hand, but I didn’t say that in class. I would like to hear what PRC people think about 大媽.

I would have hated it too if I was called 阿嬤, because it’s a term for a generation that’s older than I think of myself. It’s hard to accept that I’m not a younger generation anymore. People saying that to me would be saying that I’m old in front of me. (I think using 阿嬤 is more 親切 [cordial] than 阿媽, which I think is more for dialect use.)

I like the term 女士 [nǚshì]. It is formal, not written only, “Ladies and gentlemen,” 女士們先生們 [nǚshìmen xiānshengmen], is still being used almost in every ceremony, public event, etc. It’s respectful to call someone 女士. I learned from my father to write 女士 on envelopes if the recipients were female, like my 姐姐 [older sister][jiějie]。So, I will have no problem being called “女士”. I don’t know what my nieces in their 30s and 40s would think though.

[Another message via John Rohsenow]

This just came in from one of my former TAs, currently teaching Mandarin in Chicago as a lecturer. She is from the PRC, about 40.

This is such an interesting discussion! From my understanding, 大媽 [dàmā] is the wife of your father’s brother, so she is an older woman than 阿姨 [āyí] in mainland China. Back in 1990s, we did use 大媽 to address an over-50 woman, but nowadays, it’s regarded as offensive because the public is extremely conscious about one’s age, so you’ll use 小姐姐 [xiǎo jiějie] to address girls and younger women (even women in their 40s) and 姐 [jiě] or 大姐 [dàjiě] to older ones, or use 美女 [měinǚ] if not sure. Elementary kids may address any over-50 woman as 阿姨 [āyí], but I can’t imagine a college student does that nowadays. 阿嬤 (àhma) has the meaning of “father” in Manchu, so it’s not used in Beijing for women, even it’s an accepted term in written, but both 阿嬤 and 阿媽 have the meaning of “nanny” in Beijing, I have never heard of anyone using it to address strangers on the street, just like 阿姨 wouldn’t be used in the same situation in Shanghai. 女士 [nǚshì] is more common in business world, and more commonly used now as a spoken term, and 先生 [xiānsheng] is also used for very respectful and accomplished women, like 楊絳先生 [Yang Jiang xiansheng],林徽因先生 [Lin Huiyin xiansheng]。